All through the recent dry winter Utahns were regularly assailed with weeping, wailing, and gnashing of teeth about the impending drought crisis. The wet spring alleviated the worst concerns. But everyone in Utah knows that we're in a low water year.

This level of consciousness has led water crisis mongers among us to invoke with righteous indignation a practice now known as drought shaming. That's when they take to the modern pillory of the internet to shame those they think are obviously wasting water; running sprinklers during a rainstorm, watering in the middle of the day during peak evaporation, etc.

I myself have spouted a few hardy tsk-tsks when seeing neighbors water their lawns at such politically incorrect times. After all, nothing improves self esteem better than self righteously putting down those that fail to live up to our superior judgment. One moral superiorist that I know is seriously considering xeriscaping his yard — as if rocks and weeds will make his yard a pleasant place for his progeny to play.

My effort to avoid drought related publicity problems amounts to setting my sprinkler cycle to run at 1 am. Not only is this during the low evaporation window, it happens to be the time of day when fewest people are awake to pay attention to my sprinklers. So nobody knows when I water during a rainstorm.

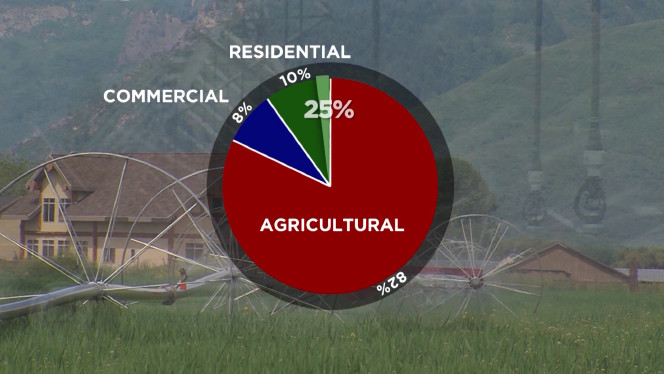

The vast majority of shaming by the self appointed drought police is aimed at residential and commercial offenders. But those that are eager to trash others for water misuse might want to pay attention to this recent KSL.com report that explains that only 18% of Utah's water is put to residential or commercial uses.

What? That's right. Only 6% of Utah's water goes to watering residential yards. 4% gets used inside our homes. Only 8% is used commercially. Where the heck does the remaining 82% of our water go? To agricultural uses.

Shamers ought to realize that even if everyone in Utah stopped watering their yards during rainstorms, quit watering in the middle of the day, only flushed their toilets after #2, took brief showers, and employed all of those other water saving tips we constantly hear about, the result would amount to far less than 1% difference in water usage.

Those sitting on their high horses about water usage seem to generally give farmers a pass. This may be due to the fact that few of these busybodies live in agricultural regions. And/or it may have something to do with the whole bucolic idea of farming and the fact that all the food we eat ultimately comes from farming.

It turns out that our farmers have a massive problem with poor water management. But it isn't really any single farmer's fault and it's difficult for a farmer to do much about it.

"We do not have a water crisis" says U of U Professor Daniel McCool, a specialist in Western water policy. "We have a water management crisis."

The problem stems from Utah's water laws, that were developed during the 19th Century when most of the state's population was actively engaged in farming. Per KSL, Professor McCool "said agriculture has so much water — and farmers get it so cheaply — that there's no incentive to conserve."

Moreover, "traditional Western water law discourages conservation." If a farmer reduces water usage through efficiency, the law punishes them by taking away their right to it. So farmers have little incentive to implement efficiencies. Vast amounts of water are wasted through evaporation and seepage from open dirt ditches because farmers have little incentive to pay the cost of implementing modern piping.

Some might be quick to point out that increasing farmers' costs would lead directly to increased food costs at the grocery store. Sort of. The market is far more complex than that. Farmers would respond to increased water infrastructure costs in a variety of ways, including shifting crops and shifting land to other uses. The rest of the world's agricultural market would react to the opportunities these shifts reveal. Some food costs would increase, but others would go down due to more efficient use of worldwide agricultural resources.

Here is how our outdated water laws work for alfalfa hay, "which consumes relatively high amounts of water." Utah farmers sell "much of the hay" to China for dairy cows. McCool says, "Farmers are using thousands of dollars of water to grow hundreds of dollars of hay" And "that's equivalent to exporting Utah's water to China with a relatively low financial return." But since farmers bear only a fraction of the cost of the water, transactions like this work financially for them.

Maybe our water laws made sense back in the 19th Century, but they hardly make sense today. Efforts to reform the state's water laws have met with little success. But that might change if more Utahns were more educated about water usage than the limited scope presented in public service announcements.

I encourage drought shamers to quit wasting their time hammering away at residential and commercial folks that use a small fraction of the state's water. Put your self righteousness to good use by focusing instead on those that could really save water in Utah.

No comments:

Post a Comment