The school system was awful for our autistic son. Some of the people in the system were fantastic. Some were extremely caring. But the system itself poorly matched our son's needs and was terrible at providing workable adaptations.

The school system was awful for our autistic son. Some of the people in the system were fantastic. Some were extremely caring. But the system itself poorly matched our son's needs and was terrible at providing workable adaptations.We were very happy to welcome son #4 to our family. His blond hair, blue eyes, cherubic face, and gravely voice were part of his endearing package. Other than the fact that he was louder than all of his brothers, he seemed pretty typical. He had a bit of a rhotacism, for which he received speech therapy at ages three and four. But otherwise he was pretty normal.

The first signs of mental health issues became noticeable when our son was in fourth grade, although, it didn't seem serious. When our son expressed suicidal thoughts in fifth grade, however, we sought professional help. Despite interventions, things went downhill toward the end of his fifth grade year, and sixth grade was a continual struggle.

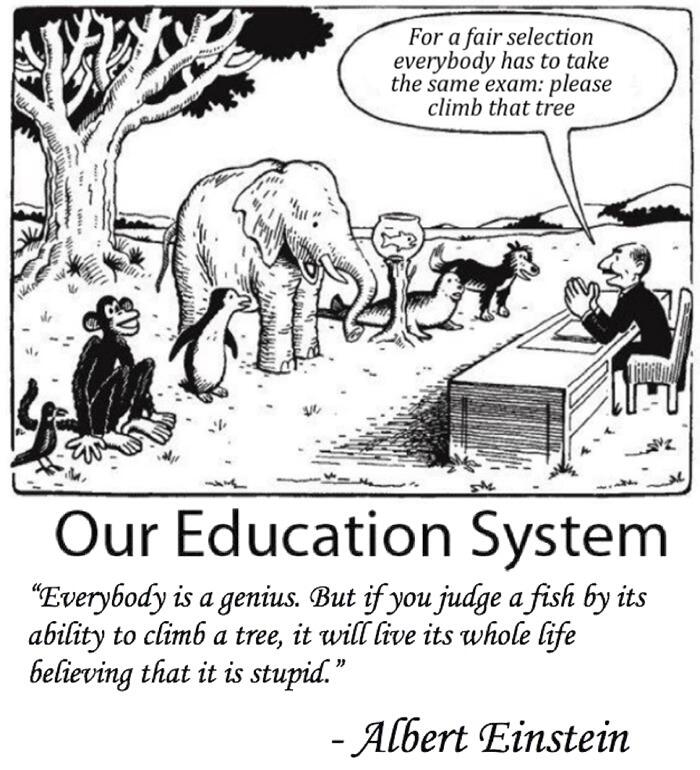

Our son now tells us that he hated school by this time because he couldn't keep up. Oh, he's very bright, but we later learned that he was running up against biological limitations. Those constraints had always been there, but they had rarely been an issue before hitting the abstract and critical thinking developmental stages.

After months of falling further and further behind, our son simply gave up hope that he could ever succeed. He reasoned that he would fail regardless of whether he did the work or not and that avoiding the work was far less stressful, so that's the approach he took. All-or-nothing thinking is common for autistic people. Since our son couldn't do it all, the logical choice in his mind was to do nothing.

We hoped that the jump to the junior high school would help our son as it had helped his older brother, but it didn't work out that way. He ended up spending three months in an intensive outpatient behavioral healthcare program that mixed schooling with mental health treatment. Managing this was quite challenging for our family, but it was also the most helpful thing for our son's condition that we had encountered.

During this period our son was evaluated by the staff at Dr. Sam Goldstein's office, which is among the best programs of its type in our region. After an extensive review, our son was diagnosed with Asperger Syndrome (AS), which people have often referred to as high functioning Autism. Some professionals today refer to this condition simply as an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), although, others find ASD to be an overly broad term.

Every case of autism is different. People think they know what to expect of someone with AS because they know somebody else with AS. But every case is unique. Our son has biological limits with processing and executive function, while his memory is very keen. One psychologist told us that it's like having the world's best solid state drive on a Windows 98 machine. You can put a lot of data on the drive and access it, but it takes a long time to process the data onto the drive and the processor can easily get overwhelmed.

"If it were only the autism we were dealing with," one professional told us, "we'd have no problem treating it. But every case of autism comes with at least one, and usually several collateral mental health issues that make each case unique and that present interesting (as in baffling) challenges to successful treatment." In our son's case that means, among other things, clinical depression and extreme anxiety, especially social anxiety.

Upon completing the behavioral healthcare program we felt that our son had the tools necessary for success ... until we came up against the intransigence of the public education system. While some people in the system are miracle workers, we also had many opportunities to work with those who were quite the opposite.

The representatives from the school district's special education department and many of the representatives from the junior high school's administration and faculty stonewalled serious efforts to get adaptations that could have actually helped our son. They especially prevented him from getting an Individualized Education Program (IEP). It eventually became clear that they didn't want the inconvenience an IEP would cause them.

It's not lost on me that these people are in a challenging situation. They have limited resources and every IEP further strains those resources. They were grappling with the realities of what they were demanded to do by law in the face of what they had capacity to do. But the result was particularly cruel and inhumane for our son.

I now realize that we should have retained professional legal help for this matter. A few years later one psychologist was beside herself that our son had still been denied an IEP. "The child is autistic!" she cried out in exasperation, "That qualifies for an IEP on its face." We finally succeeded in getting an IEP four years after our son was diagnosed. But with roughly a year and a half left in our son's public school career, the help it provided was extremely limited.

Hint: If your child has special needs, do everything in your power to get an IEP as early as possible. Being nice and cooperative in the face of bureaucratic barriers is a luxury your child can't afford. You might have to go into mama bear snarl mode in your child's best interest.

In the interim between being diagnosed with autism and receiving an IEP, our son encountered a few educators who were extremely helpful, many who were not, and yet others who were quite detrimental.

I still have a bad taste in my mouth about one of our son's junior high math teachers who is a darling of the administration, as well as many students (the ones who think math the way she does) and their parents. Although these people love this teacher, she regularly uses demeaning bullying tactics in class to deal with students who don't comprehend her narrow approach to math as quickly as she wants. Remember kids: bullying is bad unless the teacher does it.

While one math study hall teacher at the junior high was amazingly caring, her counterpart at the high school informed us in a snippy tone that she had 35 students for an 80-minute period. "That means that I have only about two minutes per period for each student!" she exclaimed. Translation: "I am nothing more than a glorified monitor who is trying to keep the kids from getting too noisy. Don't expect any real help from me. After all, I have fewer than five years left until retirement."

On the other hand, there was the high school drama teacher who went far beyond the call of duty to provide accommodations so that our son could play a role in the school play. There was the blunt spoken special education teacher who was tender on the inside but who wouldn't let our son get away with stuff he could reasonably handle.

There were also many teachers who let our son fail or nearly fail because they just didn't know what to do with him. He was always very respectful and well spoken, and he never caused problems in class, so they put no extra effort into his case.

It's astonishing how many teachers at parent conferences equated classroom behavior with academic capability. This fundamental misconception meant that the only reason many teachers could see for our son's under-performance was laziness. This isn't really the fault of the teachers, since few educators receive much in the way of mental health training (see Atlantic article). It is yet another deficiency of the system that caused particular problems for our son.

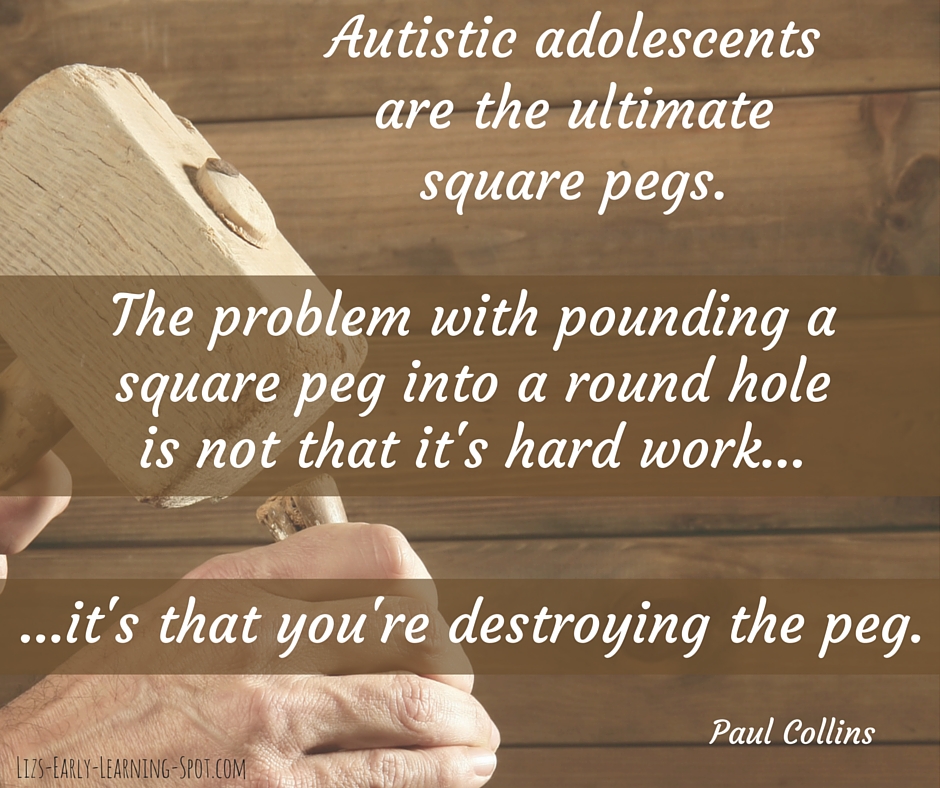

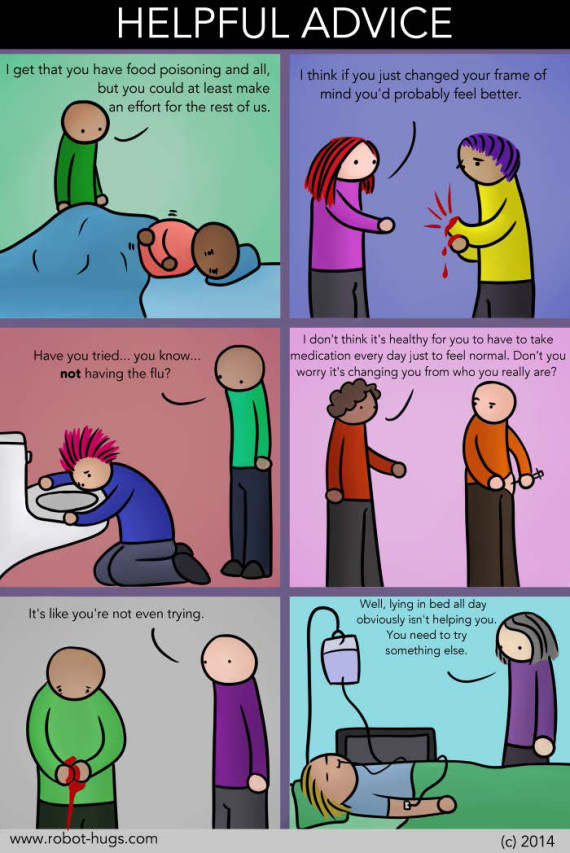

Many well meaning teachers and administrators treated our son's biological limitations primarily as a motivation problem. We sometimes did too. No one would ever do that to someone with an obvious physical impairment. Consider the comic panels to the left showing what it would be like if we treated physical health issues the way we tend to treat mental health issues.

Many well meaning teachers and administrators treated our son's biological limitations primarily as a motivation problem. We sometimes did too. No one would ever do that to someone with an obvious physical impairment. Consider the comic panels to the left showing what it would be like if we treated physical health issues the way we tend to treat mental health issues.Unfortunately, by the time our son got an IEP, his pattern of failure was bumping up against his off-the-chart level of social anxiety. He was actually not that far from completing all of his requirements for graduation. But by the middle of his senior year of high school he shut down. He just couldn't deal with the social aspects of school anymore. He had successfully completed work packets at home to satisfy some course requirements, but he could no longer bring himself to do the packets either.

During all of these years, our son has been working with qualified psychiatrists, psychologists, and therapists. We believe that drug therapy has been helpful. Frankly, it's hard to say. It makes a noticeable difference when he forgets to take his meds but part of that could be withdrawal symptoms, I suppose. None of the experts really know. They readily admit that they're just guessing, based on how patients tend to respond.

Many of the therapists our son has worked with have been great people, but I can't really say that any one of them has been particularly helpful. We believe, however, that our son's comprehensive treatment package has been helpful overall, despite his ongoing challenges.

After our son's high school class graduated without him, we discovered that this event allowed him to take advantage of a program offered by the school district to close the gap for people in our son's situation; high school seniors with certain conditions who didn't graduate with their class but who are close to completing their graduation requirements. We learned about the existence of this program purely by fluke.

Our son ended up with a handful of packets to complete. The nature of the packets made it obvious that the effort amounted to checking off a few boxes to satisfy some bureaucrats. The packets were not academically challenging for our son but quite literally amounted to psychological torture for him.

Thankfully, the packet effort has recently finished, thanks in no small part to my wife, who provided immense support. The office in charge of this kind of thing at the school district has now certified our son's accomplishment and has granted him a full fledged high school diploma that isn't some kind of equivalency certificate.

Some might look at this diploma as a consolation prize, but I am immensely proud of our son. Few high school graduates have endured the level of challenges our son has endured to earn their diploma. He spent years struggling under a system that continually beat him down and sent nonstop messages through countless subvert and overt channels, telling him that he is stupid, deficient, and unworthy.

Some might look at this diploma as a consolation prize, but I am immensely proud of our son. Few high school graduates have endured the level of challenges our son has endured to earn their diploma. He spent years struggling under a system that continually beat him down and sent nonstop messages through countless subvert and overt channels, telling him that he is stupid, deficient, and unworthy.I have deep gratitude in my heart to all who have truly helped our son along the way. Thanks to a few good people and a few obscure programs, our son finally found a path to high school graduation, despite the system's best efforts at rendering this impossible. I am especially grateful for peers who have stuck by our son, even when that kind of friendship has been very hard to maintain. I believe that heaven reserves rare blessings for such individuals.

For now our son is moving forward with a program to learn web development. We have no idea where that path will lead. I imagine that our son's journey in life will continue to be more like hiking through a trackless wilderness area than like hiking an established trail. But at least he can now move on from the inhospitable compulsory public education scrambles to the more varied climes of young adulthood.